Harry and Fritzi Goldie, Brooklyn, NY

I grew up in a suburban neighborhood a few miles north of Baltimore city that was ordinary enough, though there was very little that was ordinary about the vibes whooshing around our family’s dinner table.

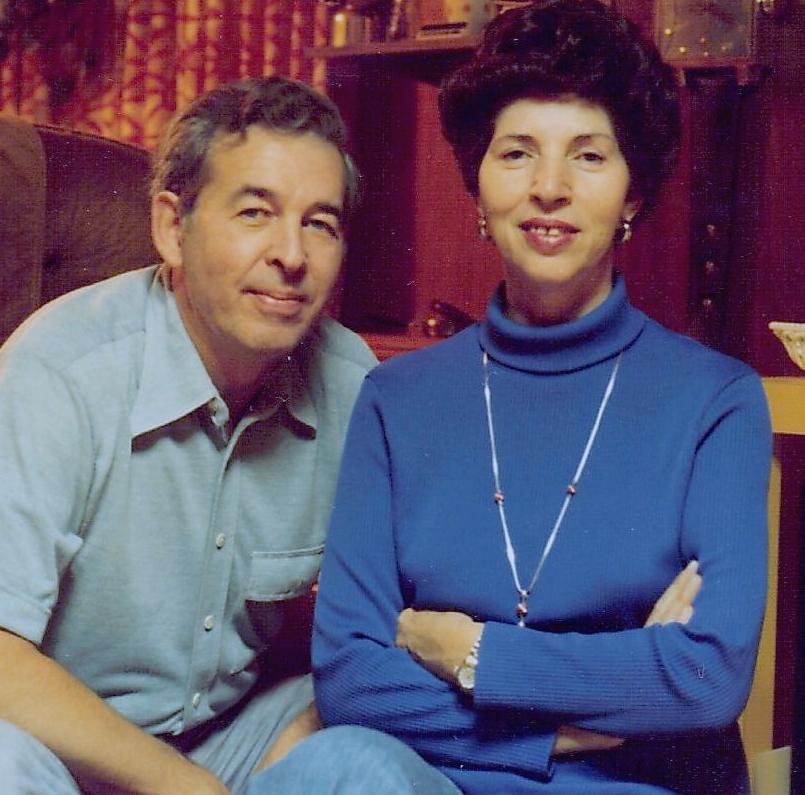

My mother Fritzi was born in the Transylvanian Alps of Romania in 1926. She and my father, Harry, were happily married for 30 years. He passed away of cancer, in 1983, at the tender age 56.

My father was raised in an orphanage in Brooklyn, New York, one subway stop away from where his mother, my grandmother, Tibbie, lived. The reason he didn’t live with her was because her husband, Joseph, my grandfather, lost his business in the stock market crash of ’29 and decided to depart the planet rather hastily, thus leaving Tibbie with no means of support.

Harry Goldie, age 16

Finding herself with three toddlers on her hands in the midst of a massive economic collapse, she couldn’t afford to raise three boys. The money ran out.

Tibbie Goldie

She decided to keep Arthur, the oldest, depositing my uncle, Buddy, and my dad, at the local orphanage. The two tykes possessed all the survival skills that any three- and five-year-old have, which is to say, virtually none at all. The boys toughed it out, surviving a string of foster homes into their late teens.

My mother, Fritzi, on the other hand, some 4,800 miles away in northern Romania, was living a very different kind of life. Hers was a fun, carefree existence. Her parents, my grandparents Rose and Wolf Perl, were loving and generous. My mother was the youngest of six (five girls and a boy), and masterful at her primary childhood occupation: dodging kisses.

The family lived in a picturesque village in Matamures County, a few kilometers south of Ukraine. The Perl children skied and hiked and swam in streams pristine and pure enough to drink right out of. Visuel de Sus was an excellent place to be, right until the Nazis showed up in 1944.

Fritzi Perl, age 16

In the run-up to the war, in the 1920’s, my mother’s oldest sister, my aunt Estie, saw disaster looming, as so many did, and sought to leave. So when she met dashing young Luis Rosenthal, a Cuban vacationing at a local hot springs, and spent some quality time with him—and when, later, he proposed to her by letter from Havana—she boarded a ship and sailed off to marry him.

Estie and Luis Rosenthal, Havana, Cuba

It’s been said that courage is doing something difficult by choice rather than out of necessity. I, for one, count aunt Estie as one brave woman for taking that one-way trip across the pond. (All turned out well.)

In May of 1944, the fateful Nazi steam trains pulled into tiny Visuel de Sus, bringing the hiking and skiing and dodging kisses to a grinding halt.

My mother’s brother, my uncle Anci, ran (literally) north into Ukraine where he became a forced conscript in the Russian army. He made it through that virulently antisemitic experience by hiding his heritage. After the war, Anci walked across a good part of Europe to Tel Aviv, where he married my aunt Rozi and had two daughters, my cousins Leah and Ziva. Ziva was runner-up for Miss Israel, back in the day.

Several of my mother’s family—my family—perished on the transport train to Auschwitz. The real tragedy of it all was that the Nazis had arrived in northern Romania in the final year of the war. One more year and my mother and her family would have escaped it.

Perl family, pre-war. Clockwise from left: Estie, Rose, Fritzi, Shari, Wolf, Anci, Susy, Piri

So it went.

Stepping off the train at the Auschwitz concentration camp in Poland, my grandmother Rose and my mother and my three aunts and 3,000 fellow Romanians were met by SS officers wielding truncheons and acting brutal and ordering them to form up into queues.

Going to “the right” meant surviving; going “left” meant death in the gas chambers. Without realizing this, my grandmother chose to go left to help a friend’s family. Rose was never seen again. My mother’s sister, Shari, and her son, my cousin, were shot by the Gestapo and perished at the camp’s entrance.

More than a million innocents died in Auschwitz in World War II — the Nazi’s insane “Final Solution to the Jewish problem.”

My mother and my aunts Piri and Susy lived in a barracks at Auschwitz for seven horrific months. You may know some of that story. If you don’t, watch the movie Schindler’s List and you’ll get the idea.

In April of 1945, the Perl sisters were sent by train to a munitions factory in Germany to work as slave labor for the Reich. But that meant staying alive.

In May of 1945, the war ended and the Perl sisters were liberated along with the rest of Europe. My mother contracted typhoid fever and was quarantined for several weeks. She suffered a high fever, which damaged her brain. In time, she discovered sizable gaps in her memory. She has told me on more than one occasion that that was a good thing.

Fritzi in France

She and my two aunts made their way to a displaced persons camp in Paris.

If God was now back on the Continent and bestowed a blessing on the Perl sisters, it came in the form of Charlie Battye, a helpful British officer who offered to help them find their oldest sister, Estie, who was in Cuba. There was a lot of good will in the world after the truth about the Camps started came out. Sargent Major Battye wrote a letter for the Perl sisters to “Family Rosenthal Havana Cuba,” hoping to make contact with sister Estie who had married Luis Rosenthal.

Harry, Cooper Union College

Luis received it. He immediately sent funds to a cousin in Paris who arranged for passage for the Perl sisters on a ship to Havana.

After the horrors they’d endured, imagine what it was like now: living in posh comfort in Tio Luis’s large house surrounded by family. My uncle was a prosperous watch maker and a distributor, and a generous and genial guy. The sisters played tennis, ate sumptuous meals and did their best not to think about the war.

Luis sought to help the sisters find husbands. He posted a letter to an old friend, a Hungarian, Alex, living in Brooklyn, New York. Alex had traveled to the U.S. and enlisted in the army during the war and was thus granted U.S. citizenship. In the letter, Alex found a photo of three young women—the Perl sisters. My mother and my two aunts.

Alex was intrigued by Piri’s image. He drew a circle around her face and mailed the photo back to Luis — and before you could say geographical undesirability be damned the couple were married and setting up house on 41st Street in Brooklyn. Right around this time, in Cuba, my aunt Susy married Tio Moises. Over the next years, my cousins started arriving in Havana — Daisy, Vivian, Robert and Lillian.

In 1952, my mother traveled to Brooklyn to visit sister Piri and met my father Harry on a blind date. He told her he was an engineer. Not true. He was just a lab tech.

Brooklyn, New York. From left: Alex, Piri, Harry, Fritzi

He wooed Fritzi by reading her the poetry of Robert Service, which was a curious choice, since Service wrote about grizzled frontiersmen like Dangerous Dan McGrew who tramped up to the Yukon searching for gold. But my mother didn’t speak any English, so it didn’t matter. Harry had a great voice. Six weeks later, they married.

My father surprised everyone, including himself, by becoming a brilliant scientist who would find fame as an inventor. But until he settled down, he didn’t know what he was capable of.

Harry, Rhonda, Warren

My parents and my sister Rhonda and I lived in a brownstone on 41st St. between 15th and 16th avenue in Boro Park, Brooklyn, a few blocks from Flatbush Avenue. It was a warm and welcoming place.

Not having much of a family, my father loved my mother’s large European clan. Everyone was tight back then. Piri and Alex and my cousins Sharon and Rita lived right across the street. I played punch ball, stoop ball and stick ball with the neighborhood kids.

Meanwhile, a different story was unfolding in Cuba. In 1959, Castro took over the country and the communists began to confiscate people’s private property. Not wanting to live under that system, my relatives left the island (another big story) and made their way to Miami.

We flew or drove down from New York to visit them every year.

Though our life in Brooklyn was safe, one could sense Europe seething below the surface. My mother mostly kept quiet about the war. My aunt Susy never said a word about what happened to her in the concentration camp.

Not Piri. Oh, no. Sometimes, at holiday meals, she would start in with the hair-raising stories. There was the one about the kapo (concentration camp guard) who made lamp shades out of human skin. And the line-ups and selections with Dr. Mengele, the mastermind of the gruesome medical experiments carried out on the defenseless inmates of Auschwitz. We kids, in our safe world, listened rapturously, taking in life lessons without realizing it.

While my father supported our family at his day job, he attended Cooper Union college at night where he earned a master’s degree in electrical engineering. In 1962, Westinghouse made him an offer he couldn’t refuse. He moved us to Randallstown, Maryland, just north of Baltimore, not far from his new job.

Randallstown, Maryland

My parents loved their ordinary suburban existence. In fact, all they wanted was ordinary. On the outside, they were secure and happy. On the inside, the currents of their traumas flowed unseen.

What was interesting, to me, was that my parents were total opposites. Yet enamored of each other. If they were seeking love online today, they would have surely have clicked to the next profile.

Not long after my father logged his 35th U.S. patent for yet another invention that would make Westinghouse millions (while he drew a modest salary) he was diagnosed with colon cancer. He died the way many cancer victims do: diminished, drugged, shockingly different from the way you knew them. My mother was at his side every day, often sleeping in his hospital bed with him.

Many people loved my father. Most of all my mother, who would sometimes speak to him in the early morning hours, while lolling in the hypnogogic state between dreaming and waking, when the line between what’s real and what’s wished for blurs, and maybe isn’t important at all.

They’re gone now, the survivors. But their mark on us, the next generation, will live on through us and our children.

2015

Aunt Piri passed away in 2011 at the age of 90. Fritzi passed away in 2016, also at 90. Estie passed away in January 2018 at 104. Susy passed away in March 2018 at 94.

Read more: A History of the Perl Family.

Portfolio > Essays